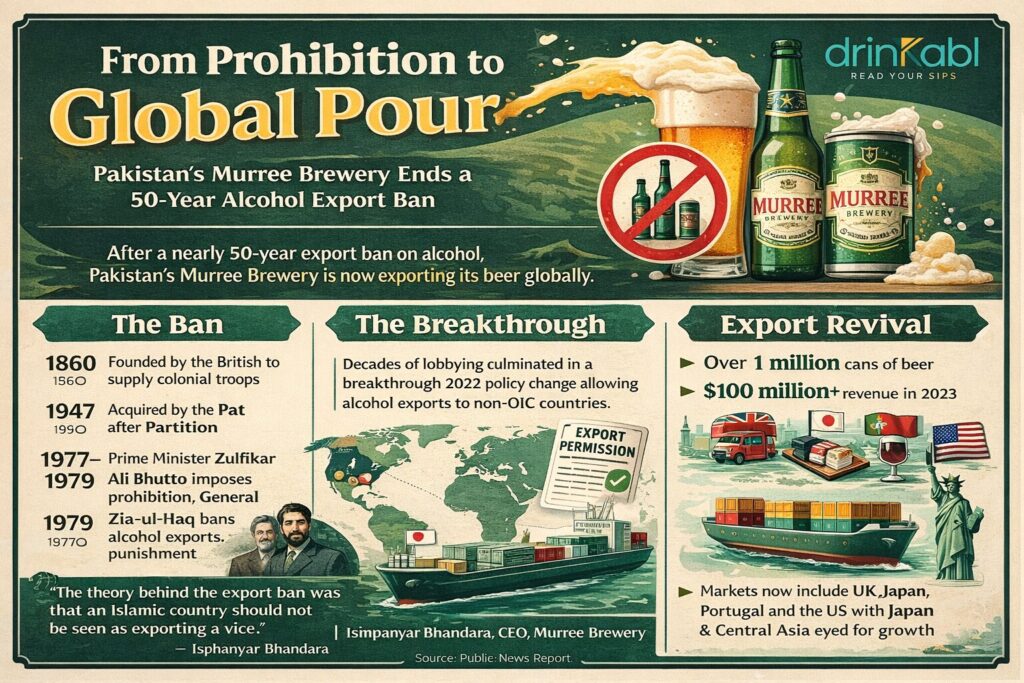

RAWALPINDI, Pakistan, More than a million cans of beer roll off the production line every month at Murree Brewery’s factory in this bustling city near Islamabad. For most of its 165-year history, almost all of it stayed inside Pakistan’s borders. Now, finally, the world is getting a taste.

After a ban that stretched nearly five decades, Pakistan’s oldest and most storied brewery is exporting alcohol again, shipping beer and spirits to the United Kingdom, Japan, Portugal and beyond. It is a quiet but remarkable milestone for a company that has spent generations navigating one of the most unusual paradoxes in the global drinks industry: thriving in a country where alcohol is officially forbidden for 97 per cent of the population.

“The theory behind the export ban was that an Islamic country should not be seen as exporting a vice.”

— Isphanyar Bhandara, CEO, Murree Brewery

The brewery was founded in 1860 by the British to supply colonial troops stationed in the hill towns above what is now the Pakistani capital. After Partition in 1947, it was acquired by the Bhandara family, members of Pakistan’s tiny Parsi minority, descendants of Persian Zoroastrians who are not bound by Islamic prohibitions on alcohol. That heritage proved decisive to the company’s survival through decades of tightening regulation.

The decisive blow came in 1977, when Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto imposed nationwide prohibition. His successor, the military dictator General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, went further, introducing lashing as a punishment for drinking. Exports were banned on the grounds, as CEO Isphanyar Bhandara now recalls, that the Islamic Republic should not be seen trafficking in vice. The brewery was allowed to keep operating domestically, serving the small pool of non-Muslims and foreigners who could legally buy alcohol with government permits, but its international trade was finished.

For a generation, Murree Brewery had been selling to India, the United States, and even Afghanistan. That market vanished overnight.

“Initially, we were not confident that all of the things will go smooth.” — Ramiz Shah, Export Manager, Murree Brewery

What followed was a decades-long campaign by the Bhandara family to reverse the ban. Isphanyar’s father, Minocher, who sat in parliament and served as minority affairs adviser to the very government that had banned exports, lobbied persistently for reform. When Minocher died in 2008, Isphanyar took up the cause. The breakthrough came quietly: a 2022 revision to Pakistan’s export policy opened a pathway for alcohol shipments to countries outside the 57-member Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. Permissions, however, are not automatic, each producer must navigate a series of departmental clearances before a single case can leave the country.

Murree’s first post-ban export shipment, a test run of beer destined for the UK, went out last spring. Portugal and Japan followed. The company recorded its strongest financial year yet in 2025, with revenues exceeding US$100 million, and export manager Ramiz Shah, cautious at first , says the process has gone more smoothly than expected.

The economics driving the government’s decision are straightforward. Pakistan’s economy has been under severe strain, and foreign currency is desperately needed. Domestic alcohol consumption offers almost no room for growth: non-Muslims account for less than four per cent of the population, and while bootleg alcohol circulates widely, through informal networks and unlicensed shops in Sindh , that market generates no tax revenue and no hard currency. Exports do.

Murree also has a structural advantage that few other brewers can claim: its ingredients are sourced locally, keeping production costs low and giving it a natural price competitiveness in international markets.

The company is now focusing on Central and East Asia, particularly Japan, as well as Europe and the United States, markets where it has already developed distribution relationships through its non-alcoholic exports of malt beverages, juices and bottled water, which currently generate around US$30,000 per month. Those existing channels are easing the introduction of its alcoholic products.

Pakistan is also home to Hui Coastal Brewery and Distillery, a Chinese-run operation that began production in 2021 primarily to serve Chinese workers in the country, but it remains restricted to domestic sales. Analysts believe that if Islamabad extends export rights to additional producers, Pakistan could carve out a genuine niche in the global drinks market, an unlikely but not implausible prospect for a country whose government once considered beer a vice too shameful to ship abroad.

For now, Murree Brewery is proceeding carefully, with no government revenue targets attached to the programme and no guarantee that the political winds won’t shift again. The family has waited nearly fifty years for this moment. They are in no rush to squander it.

Murree Brewery is publicly listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. The company also holds a US retail presence, having opened a flagship store on Park Avenue in New York in 2014.